Sam Chang / Onboarding

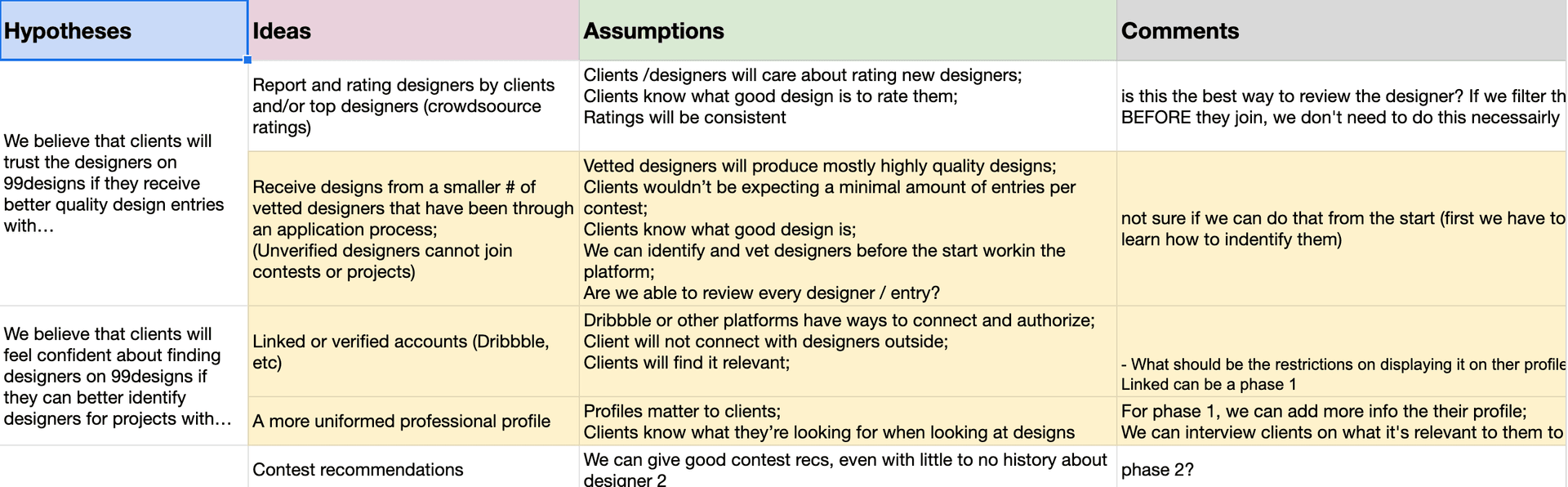

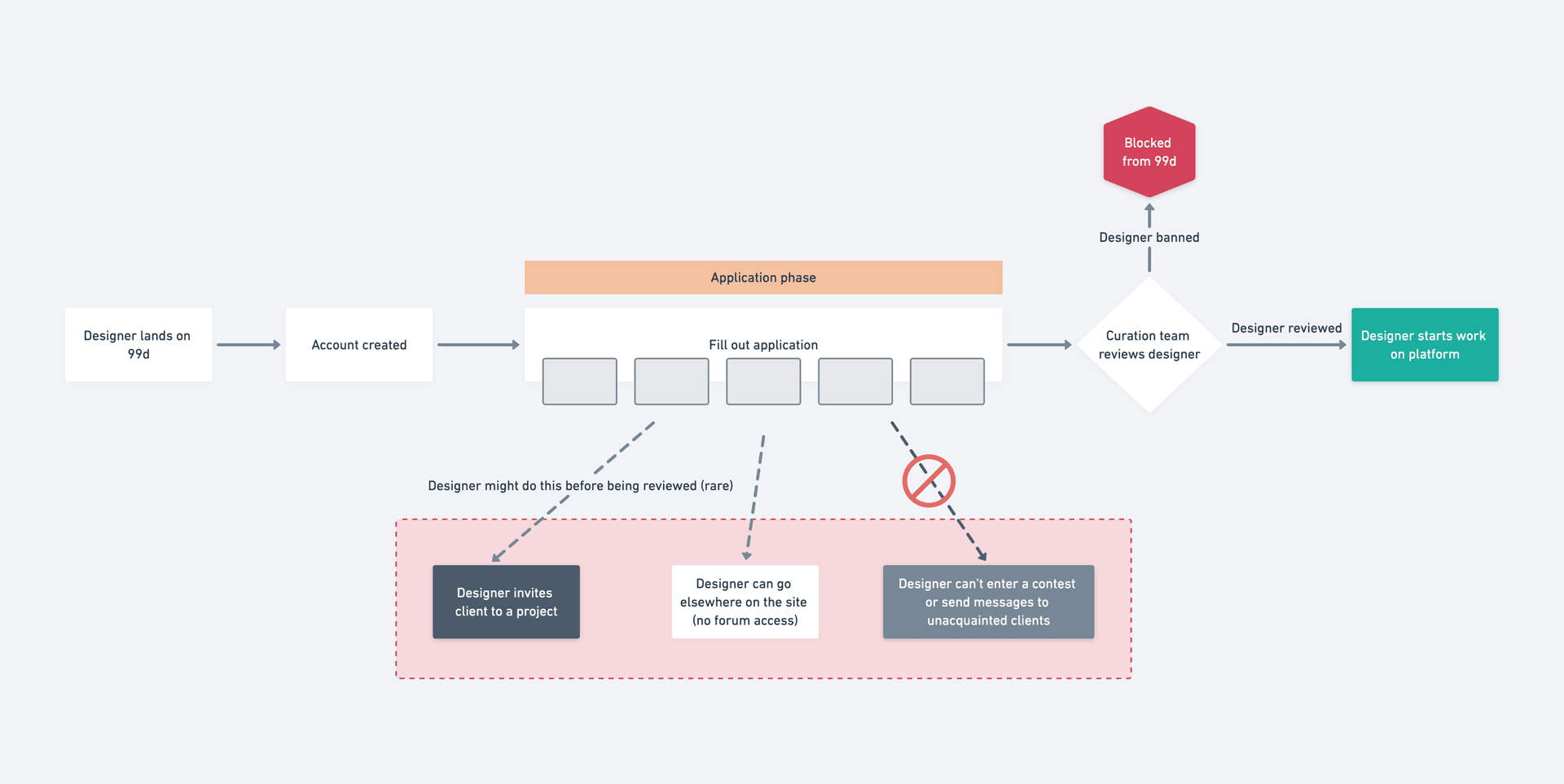

The designer community is 99designs’ greatest asset. Over the past 10 years 99d has invested in building a professional design community. An example of that investment is the creation of a Curation team—a team dedicated to ranking, sorting, banning, and promoting designers.

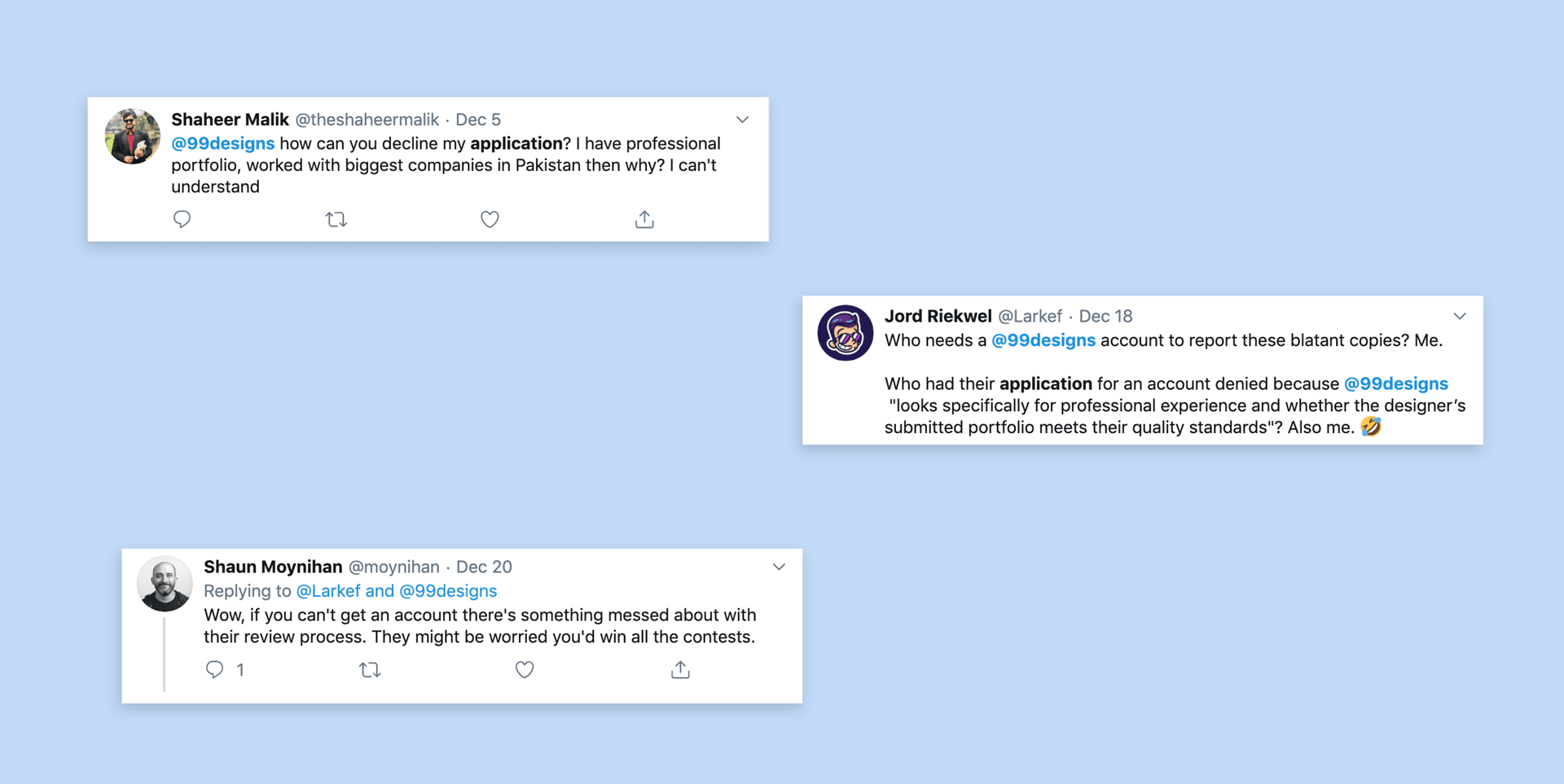

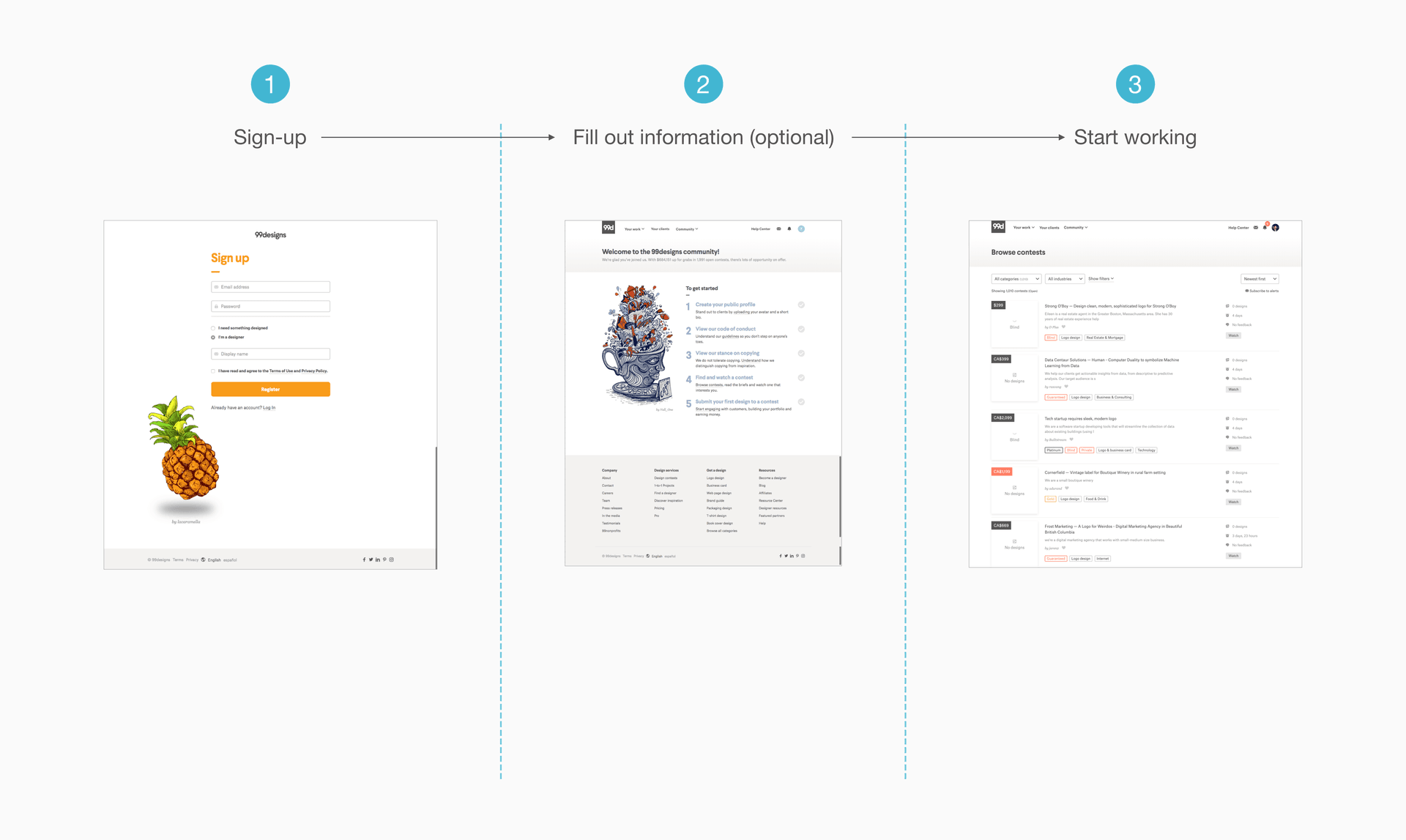

Before launching this project, 99d was open to any designer—which was pretty great. It gave everyone an opportunity to "make it" in design.

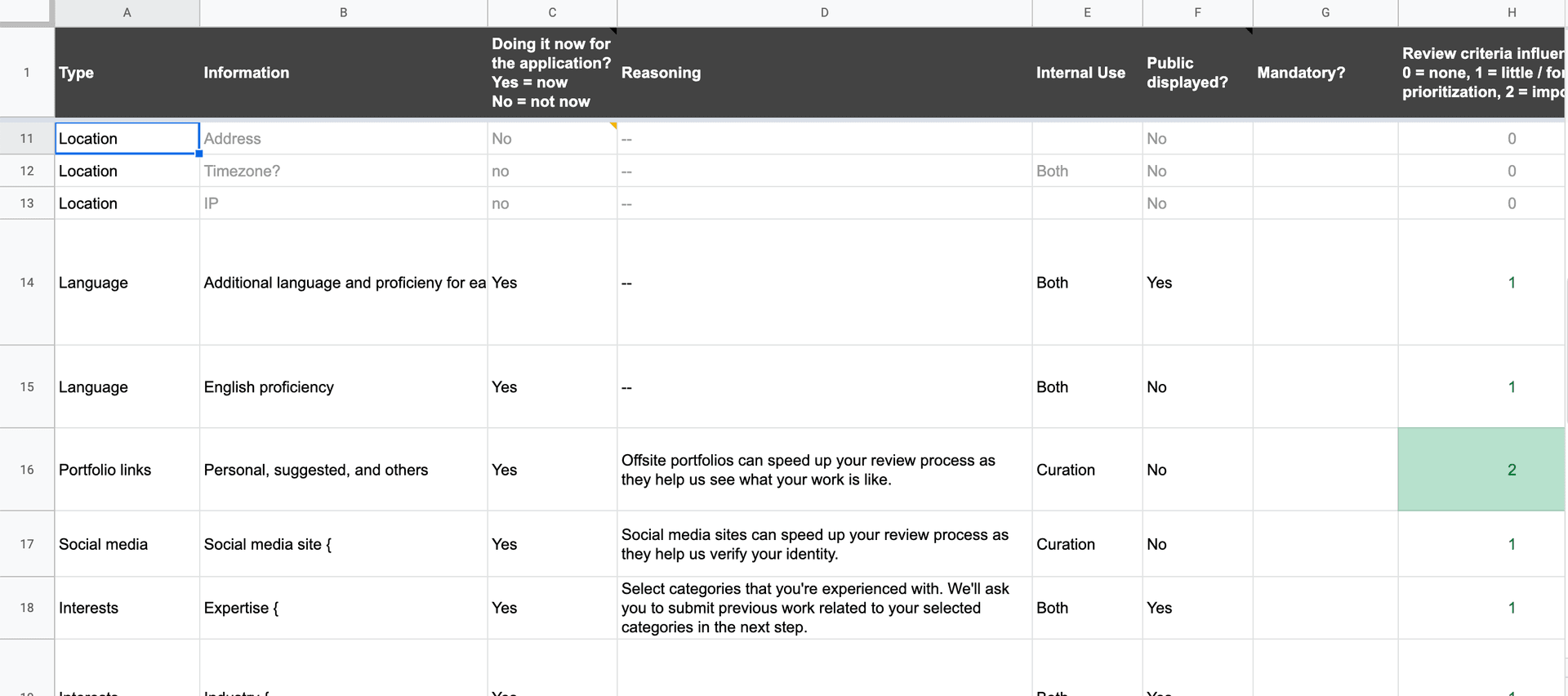

But this also meant that we didn't know anything about these designers until they started work on our platform.

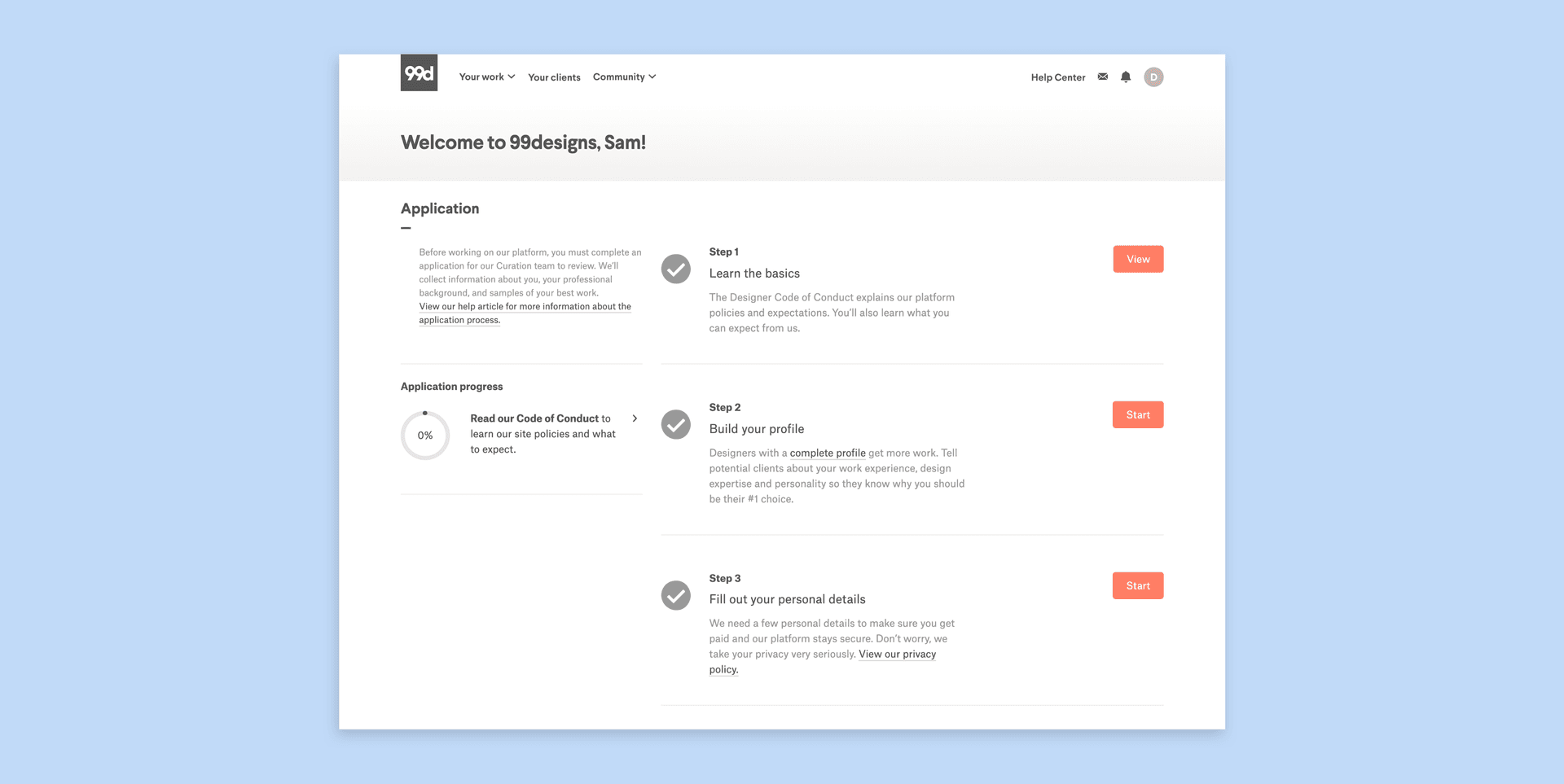

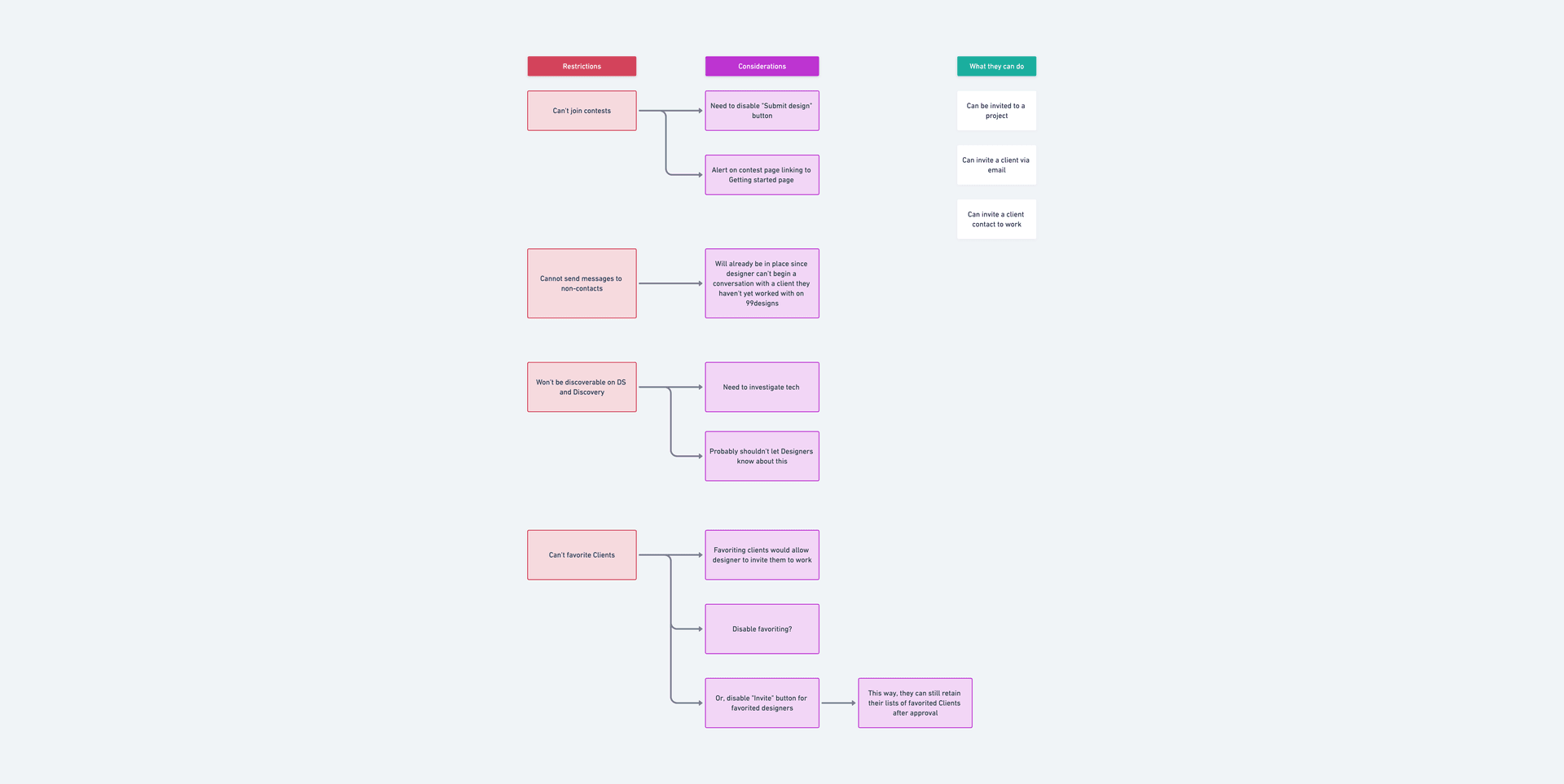

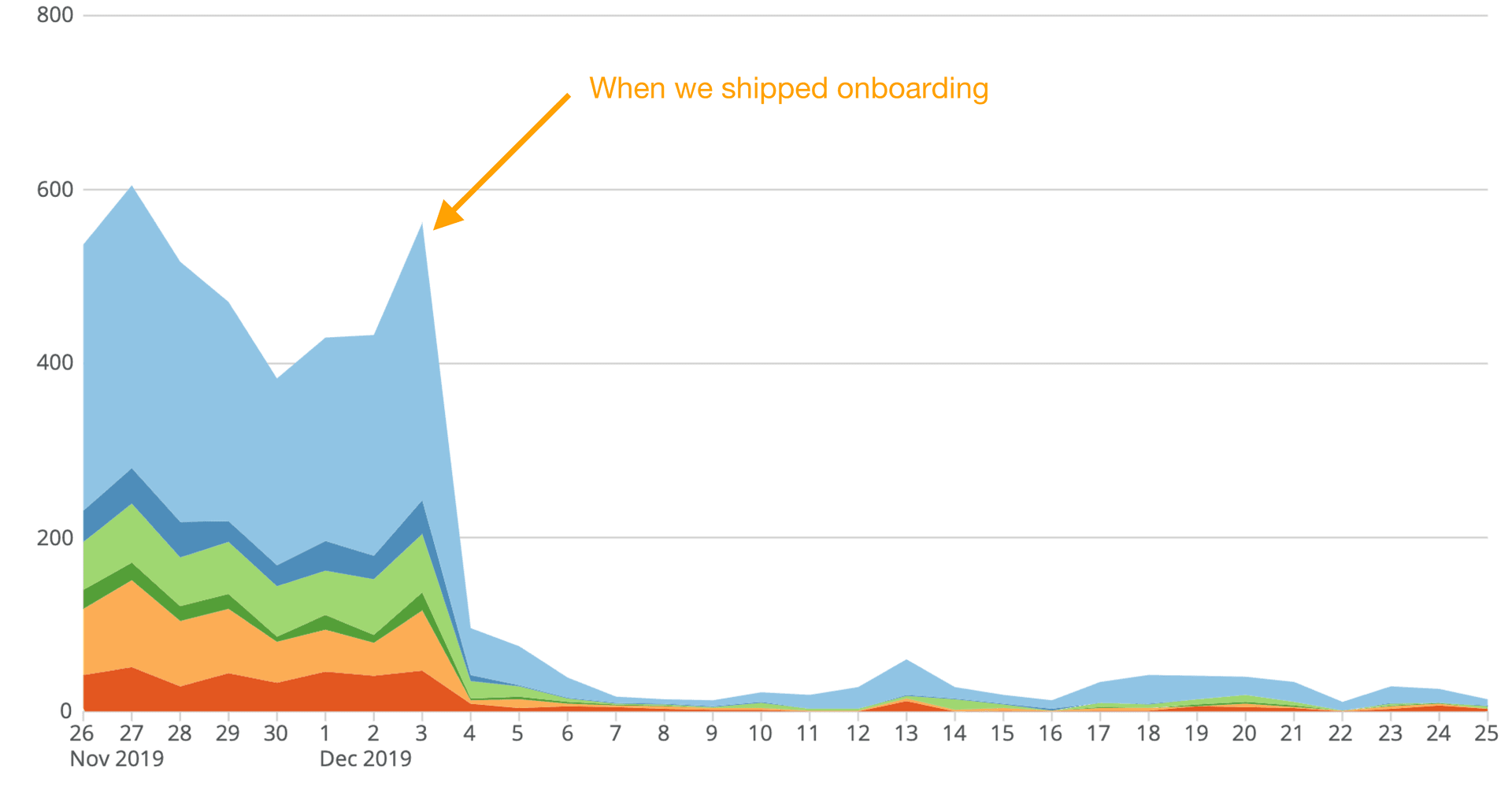

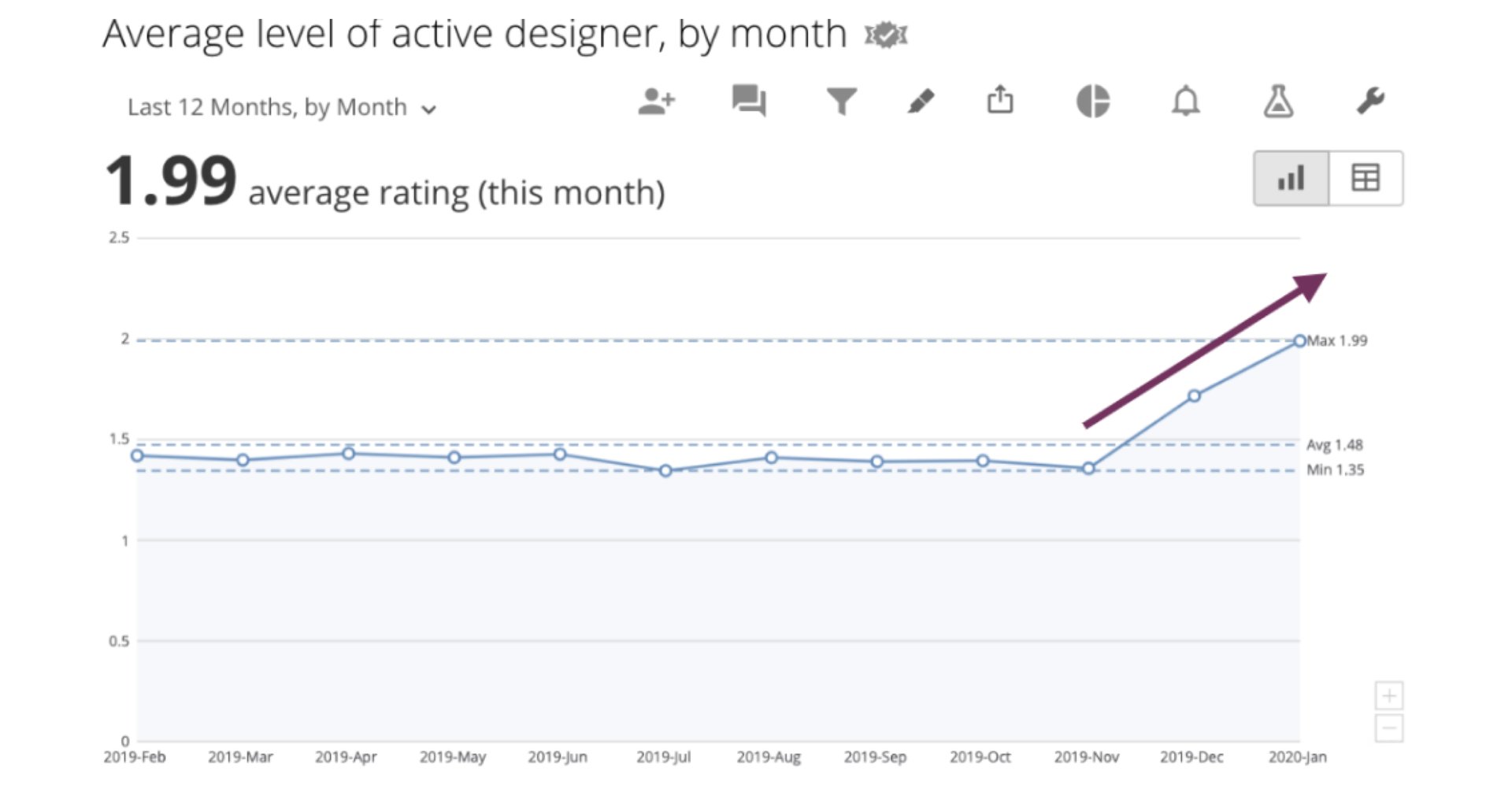

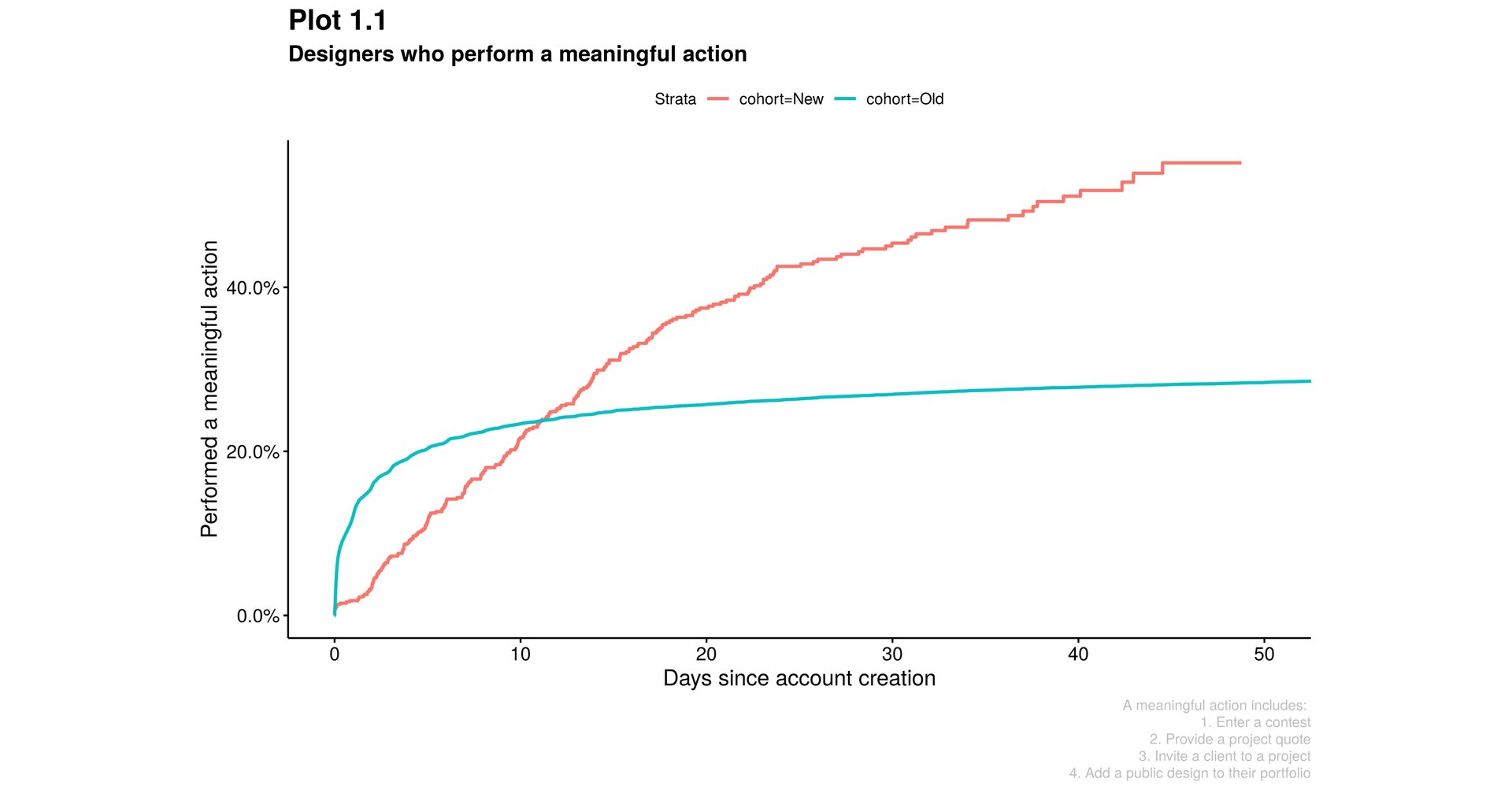

Unfortunately, most of the designers who sign up are banned due to the low-quality work they produce. This project aimed to expedite the progression for qualified designers while identifying and blocking the bad actors who don't contribute positively to our community.

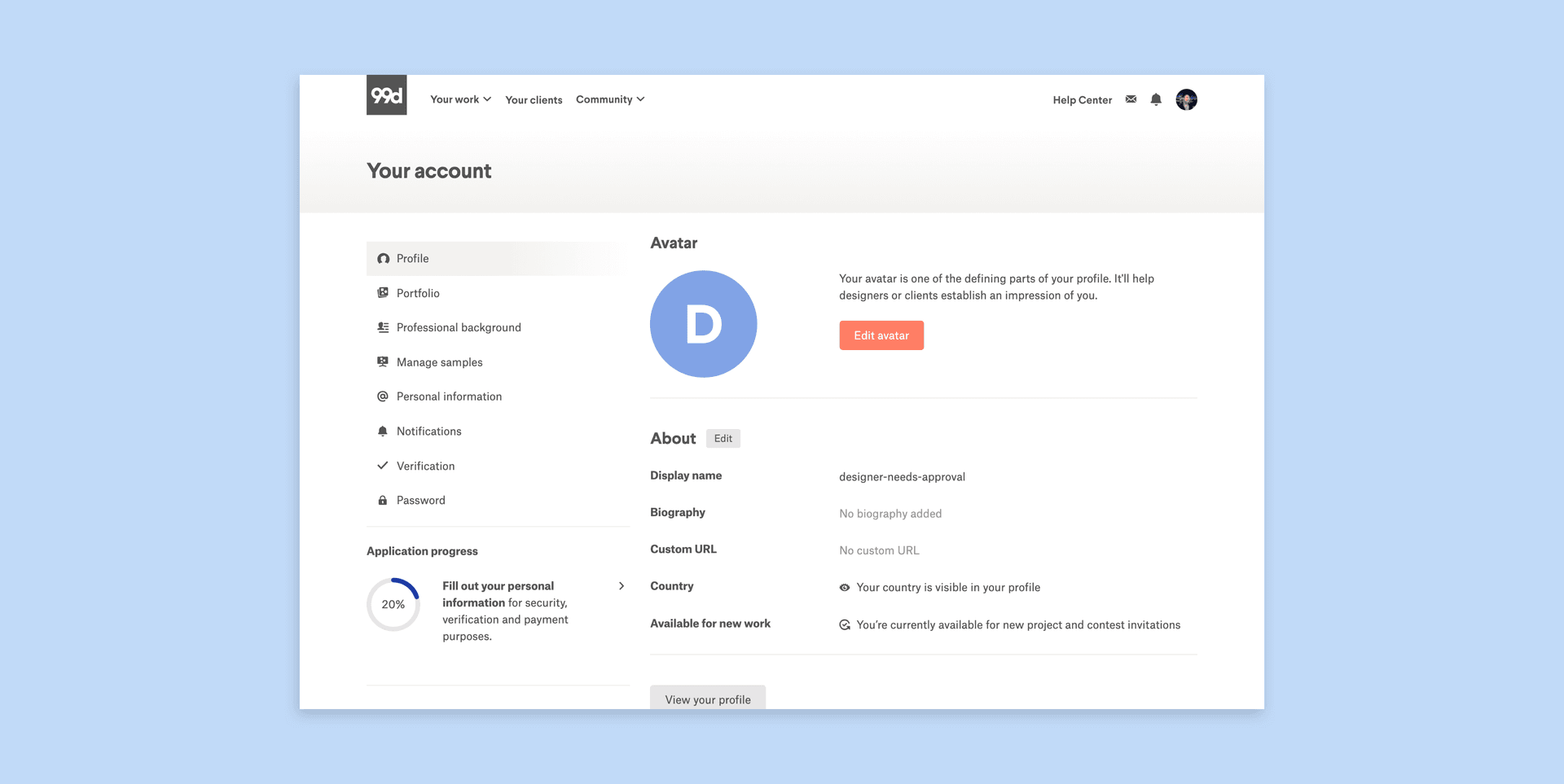

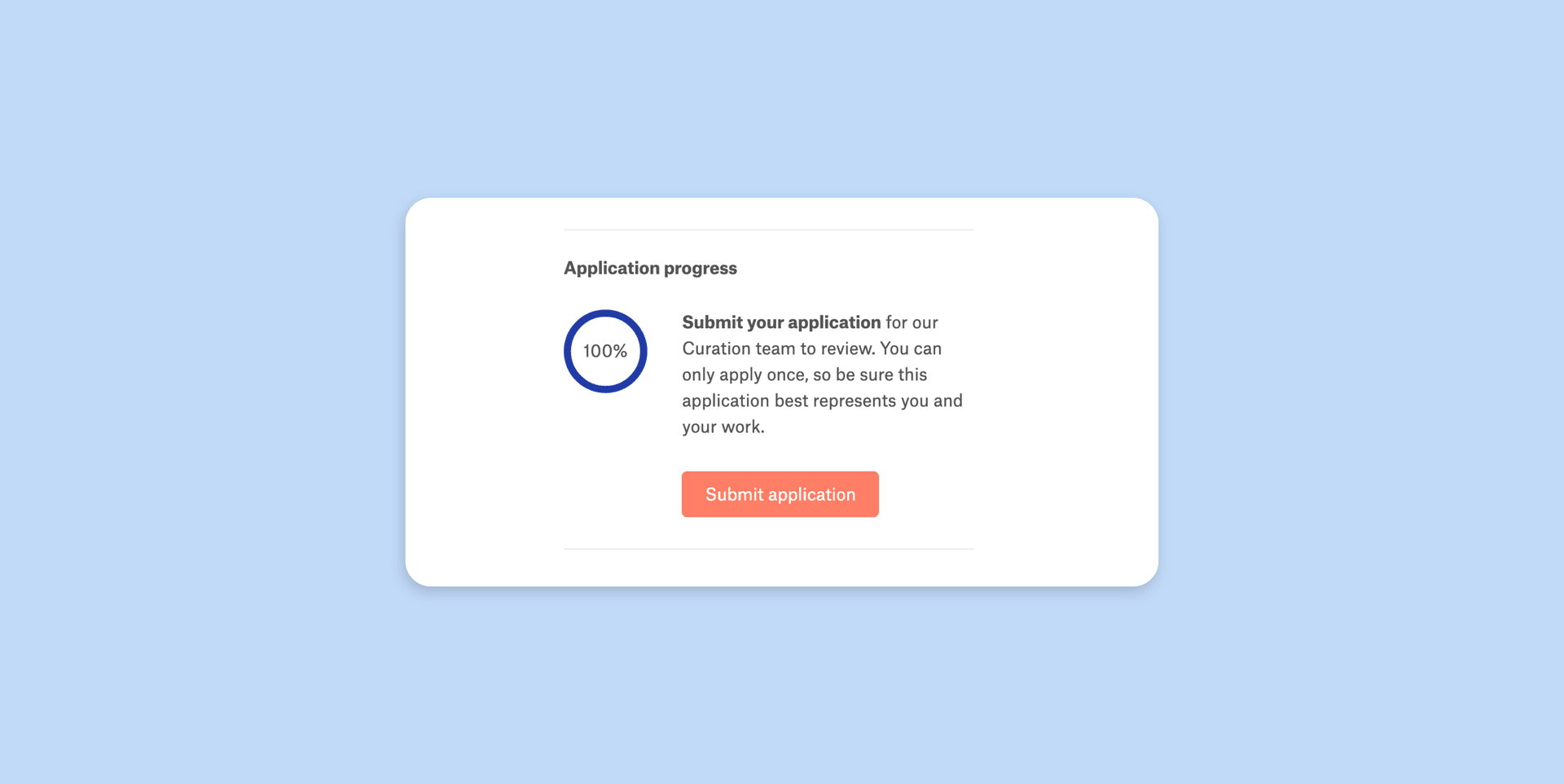

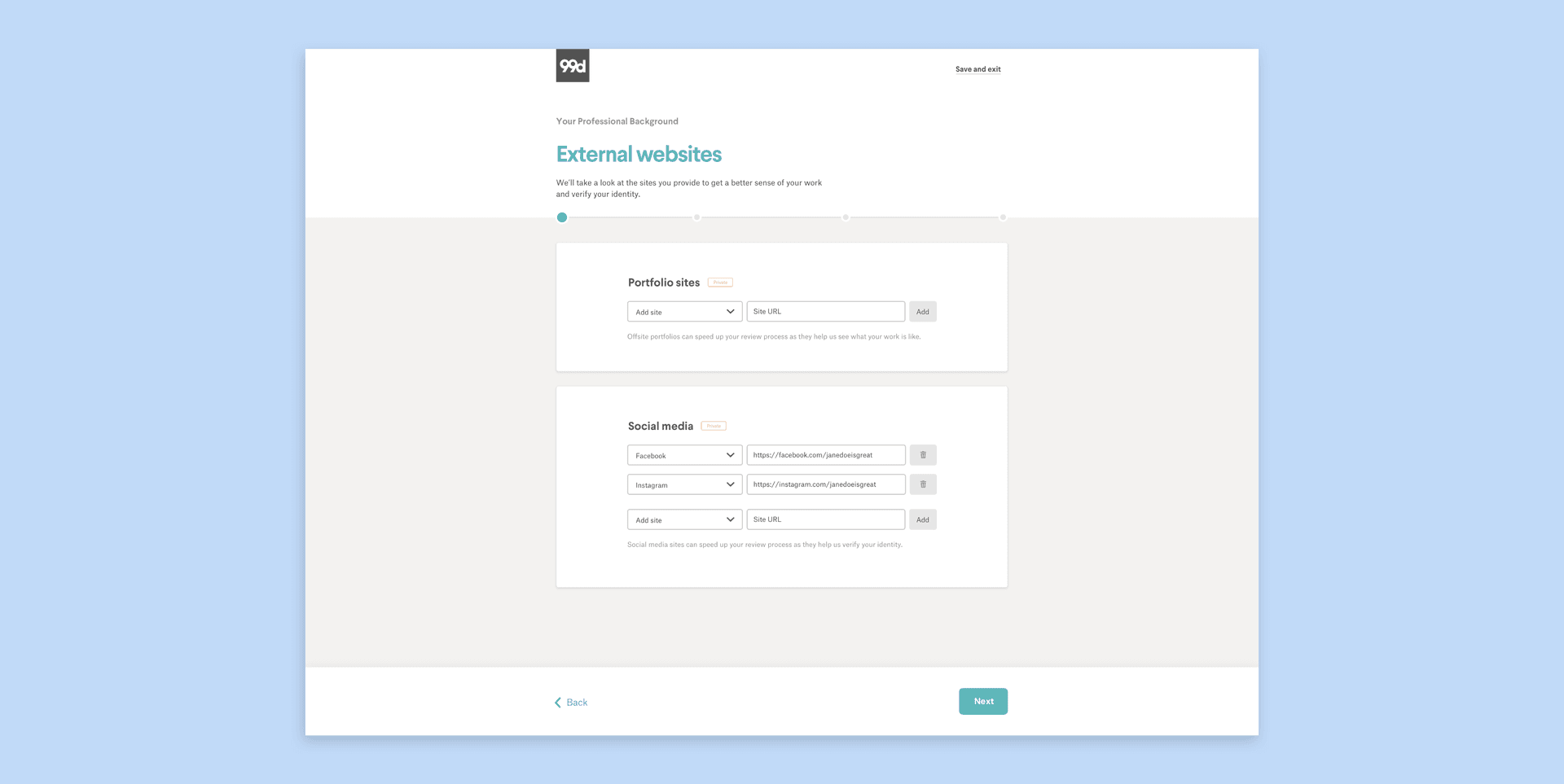

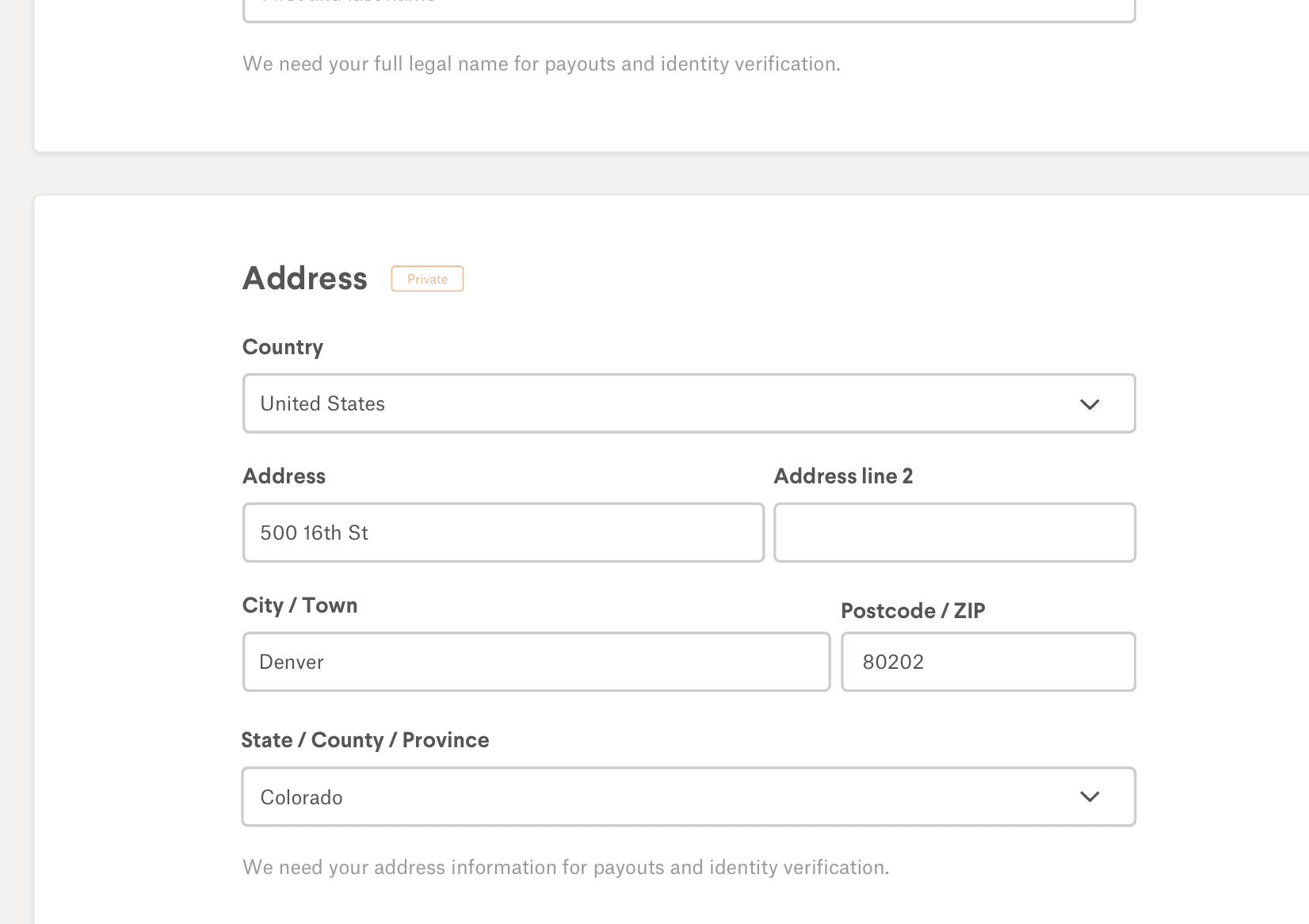

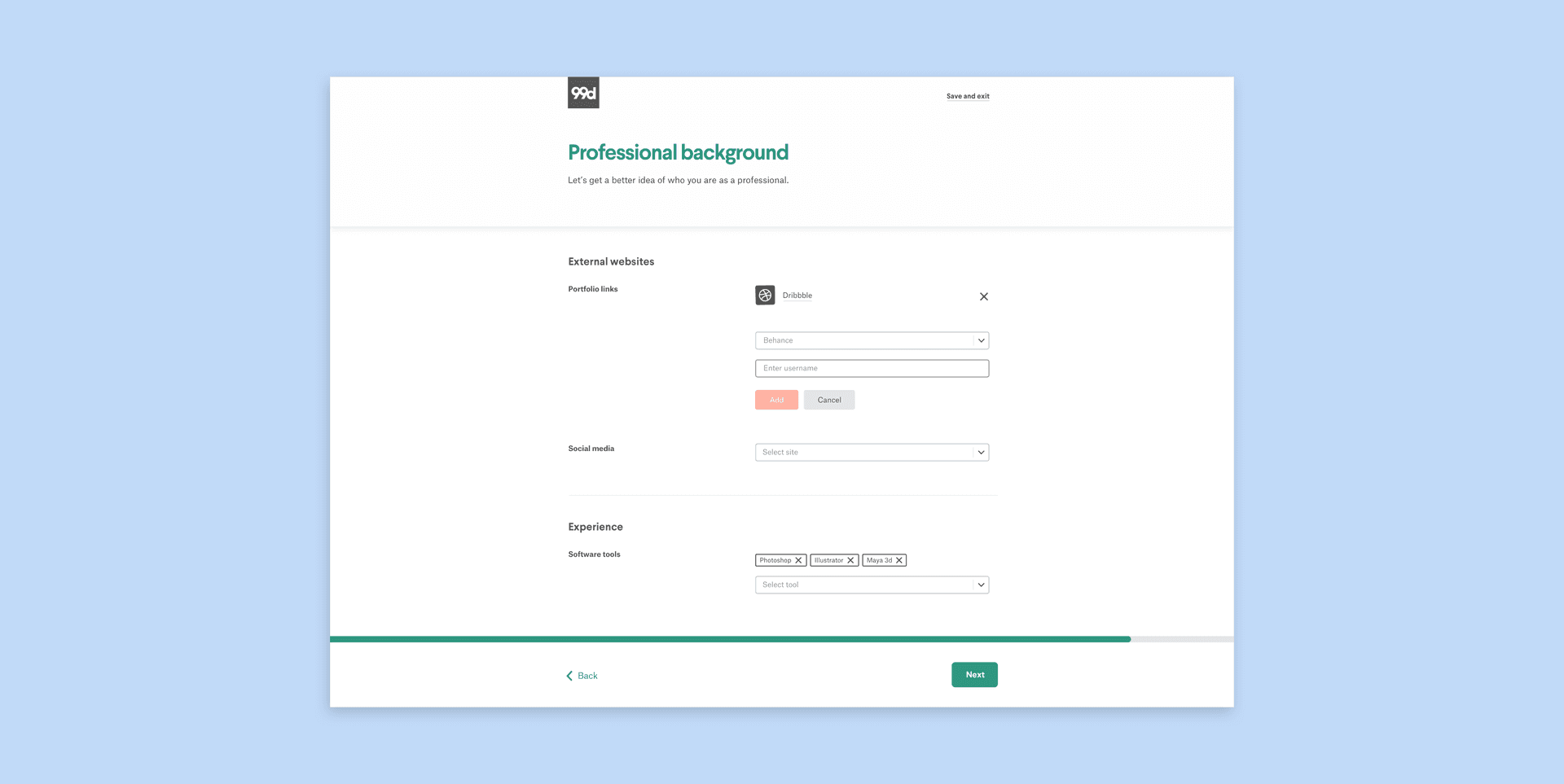

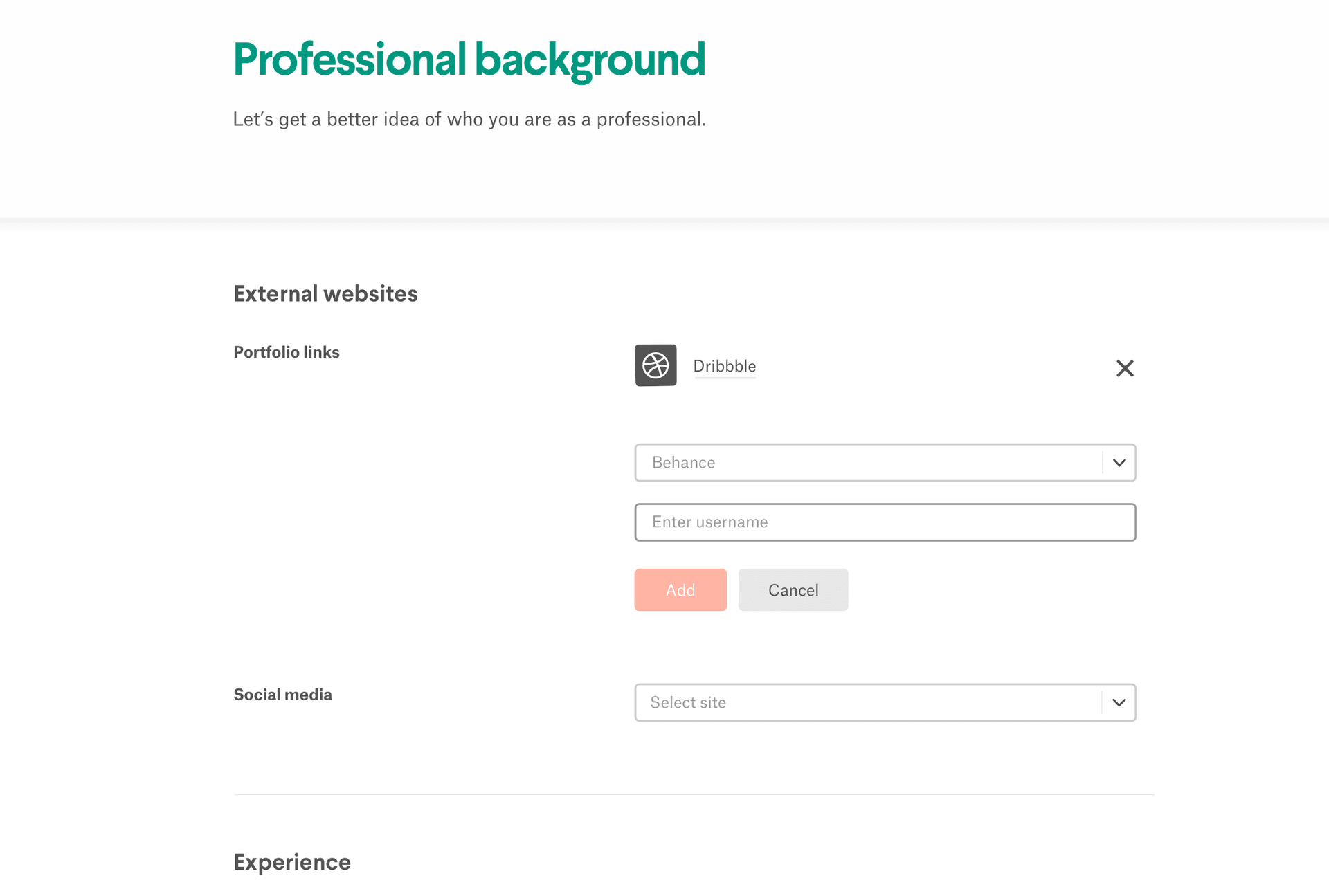

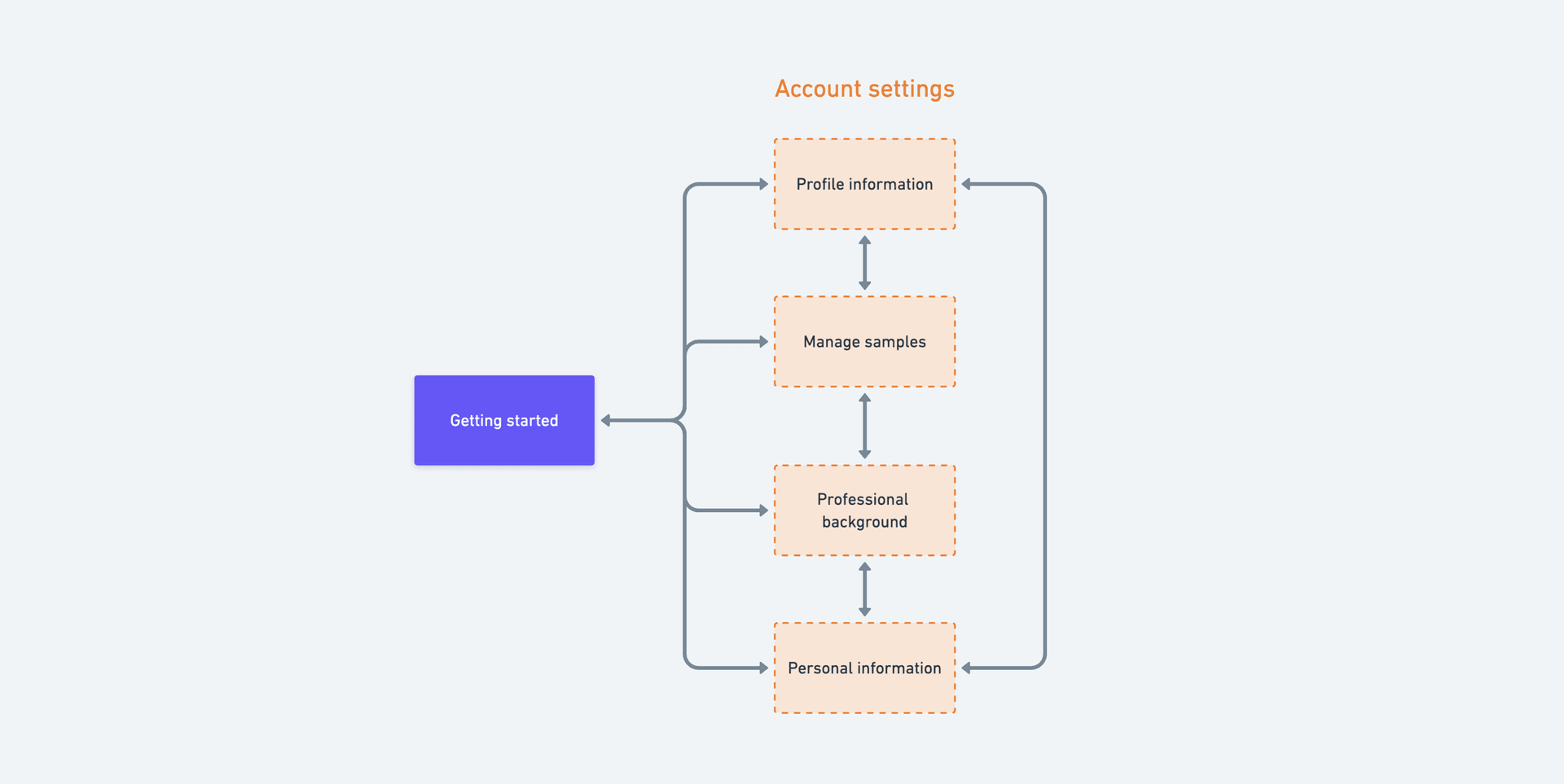

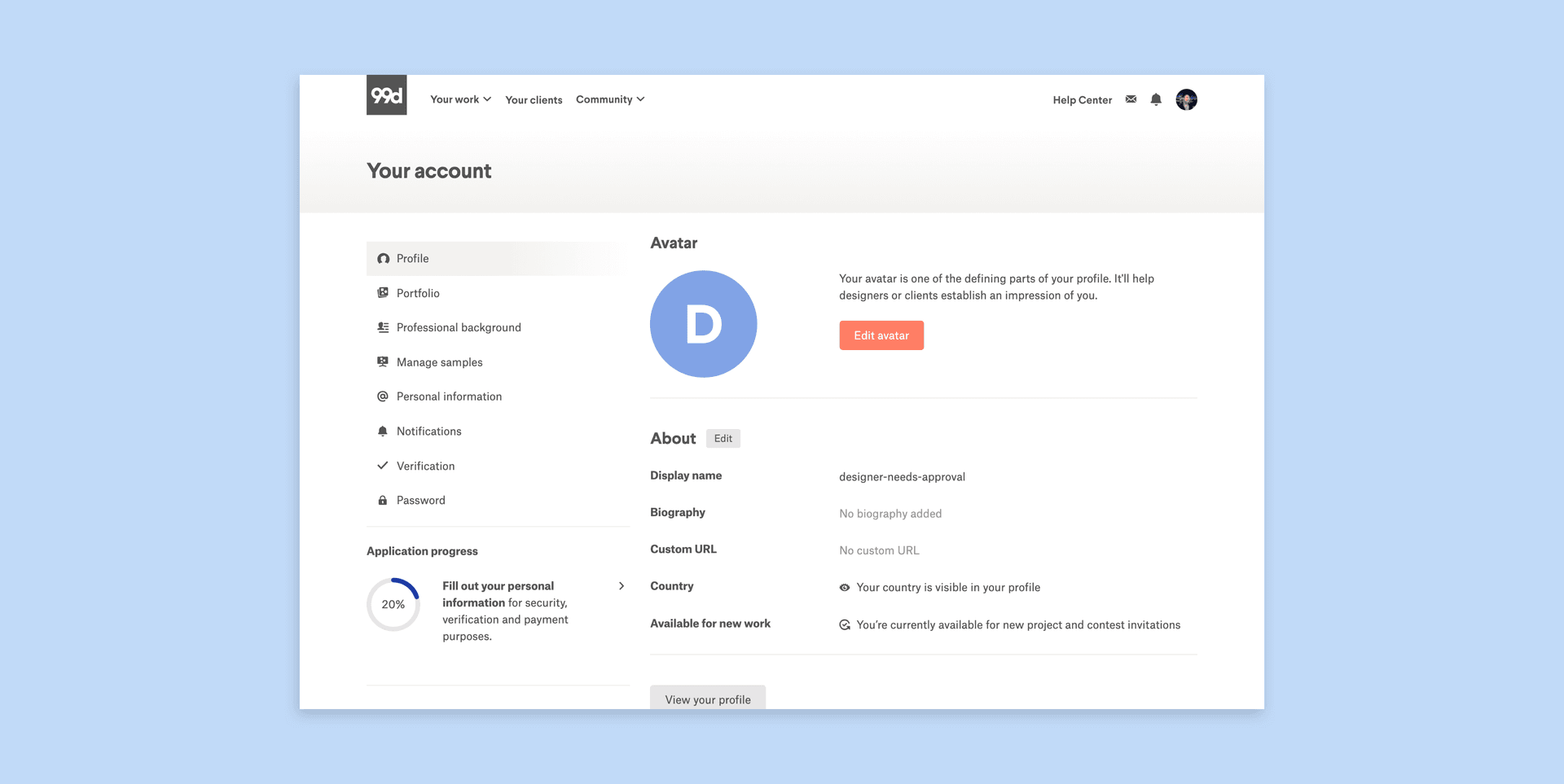

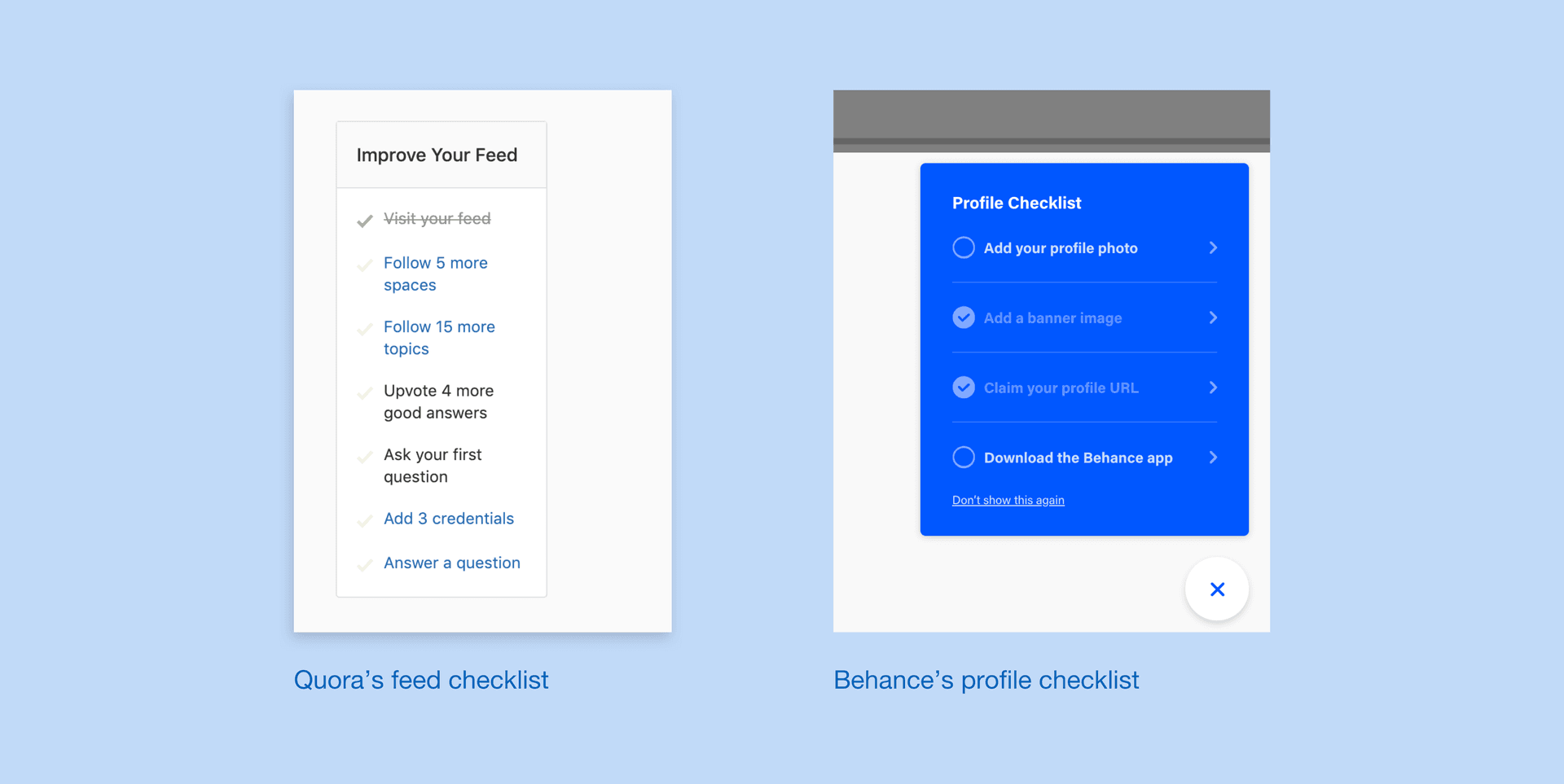

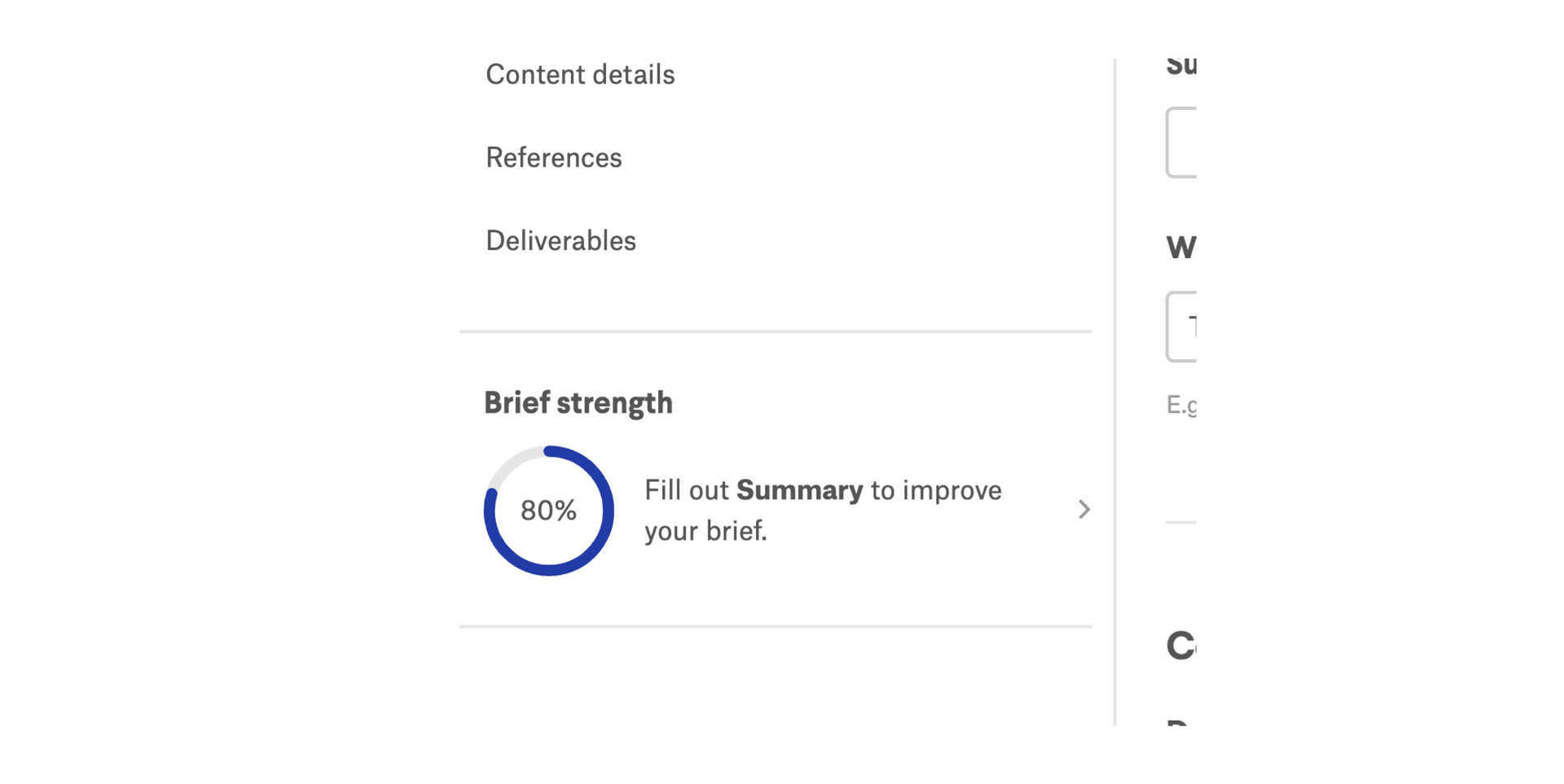

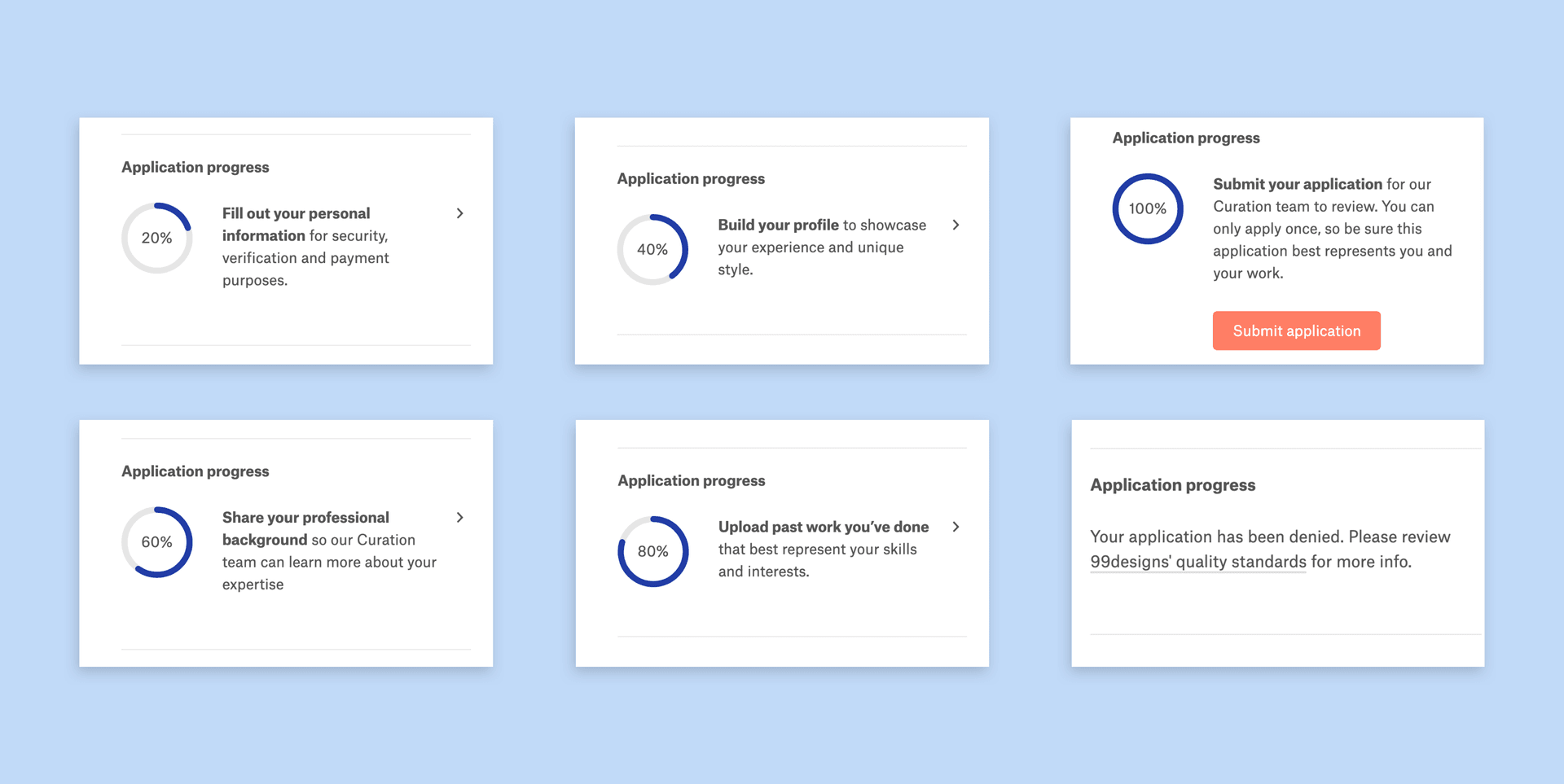

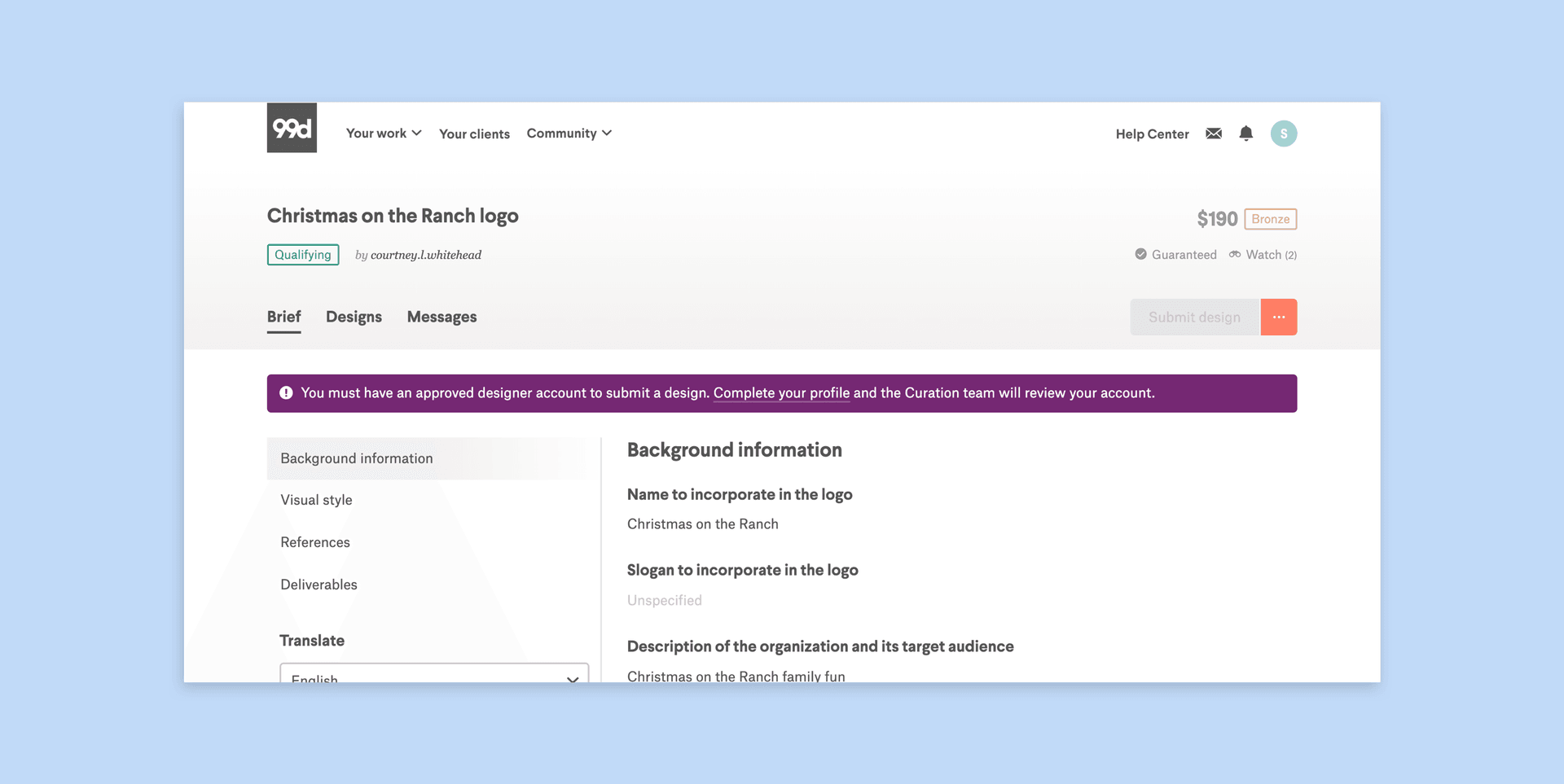

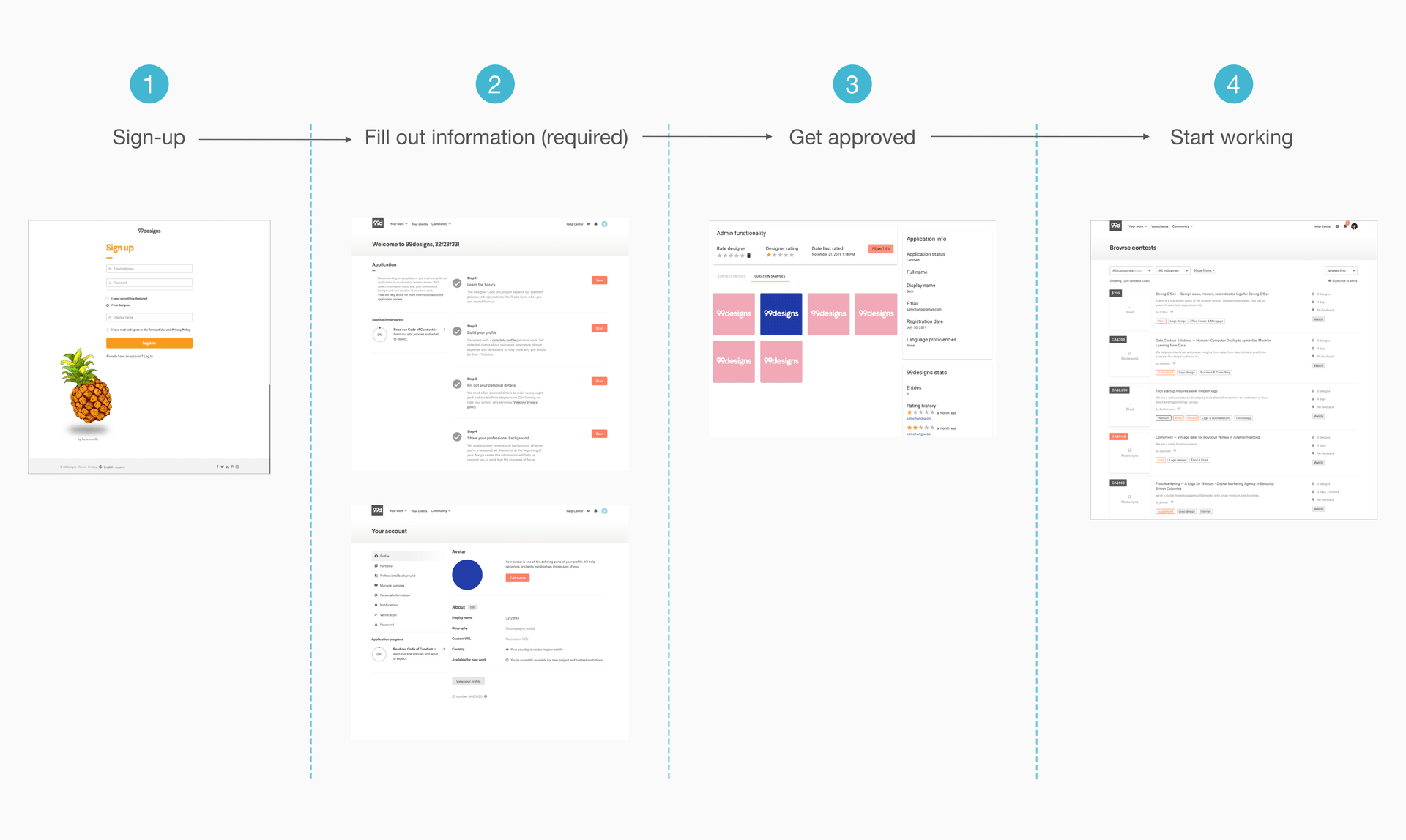

A fundamental shift in how designers join 99d, this new onboarding process will guide designers towards success and improve the quality of our design community.

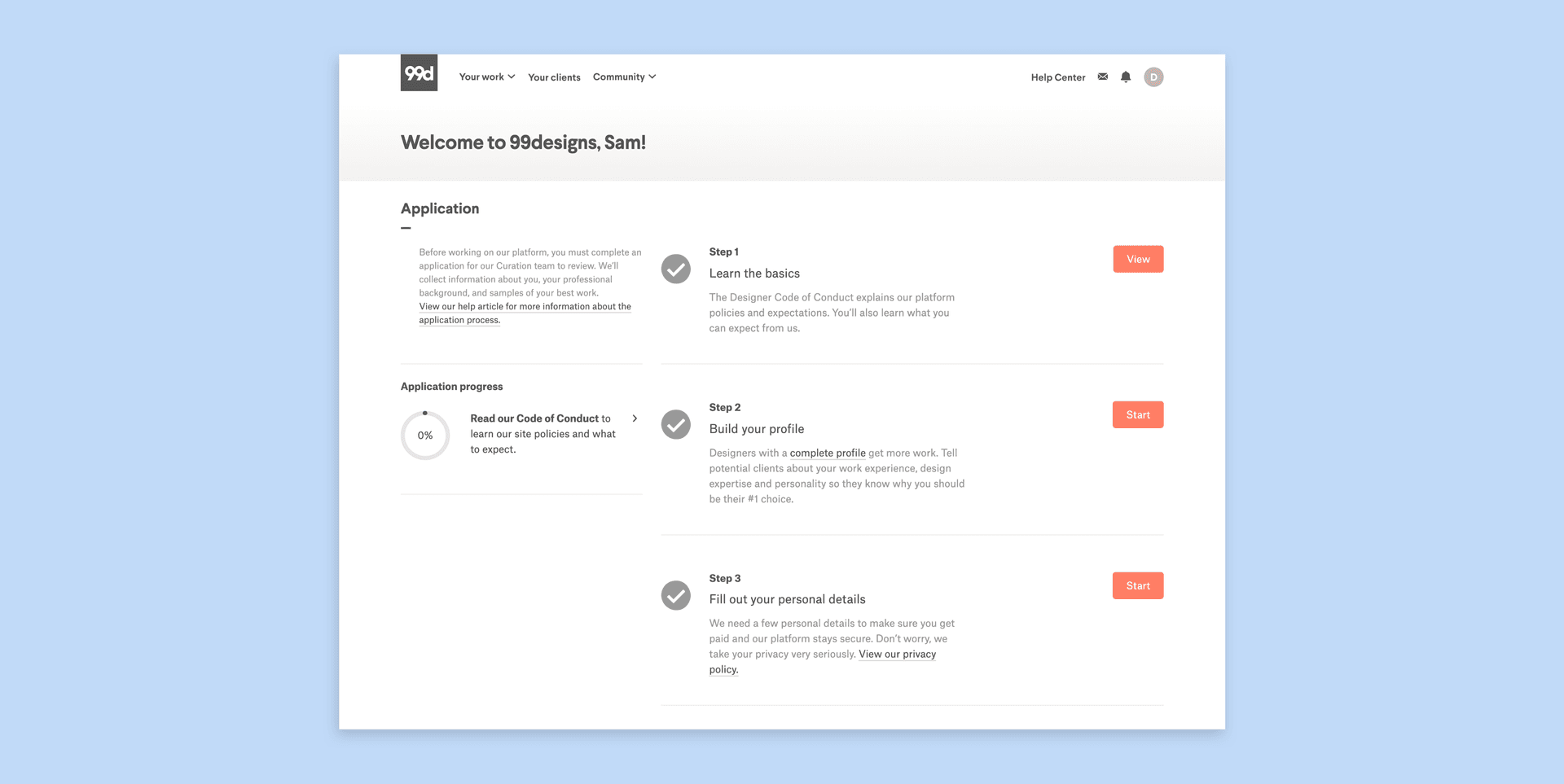

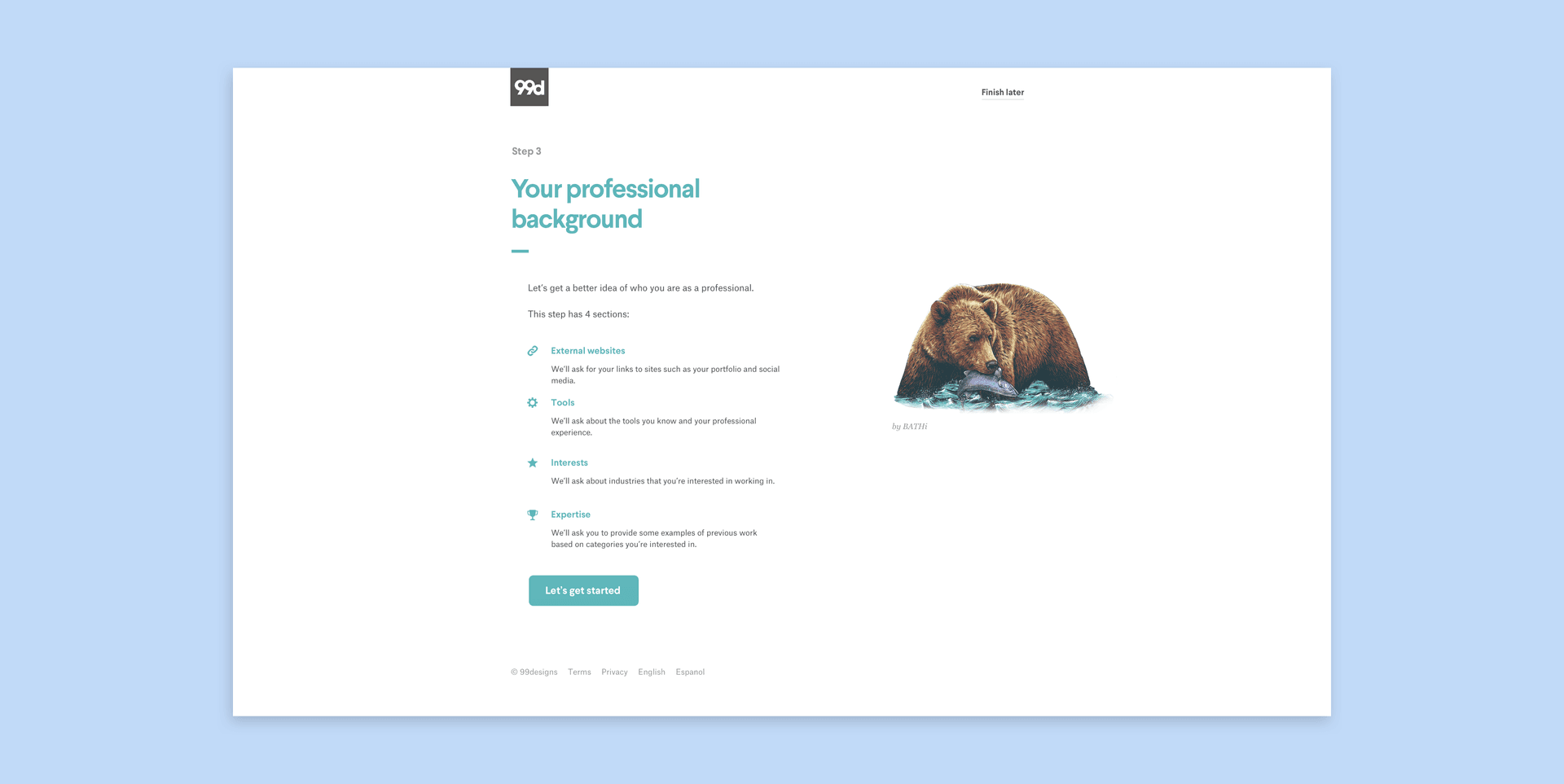

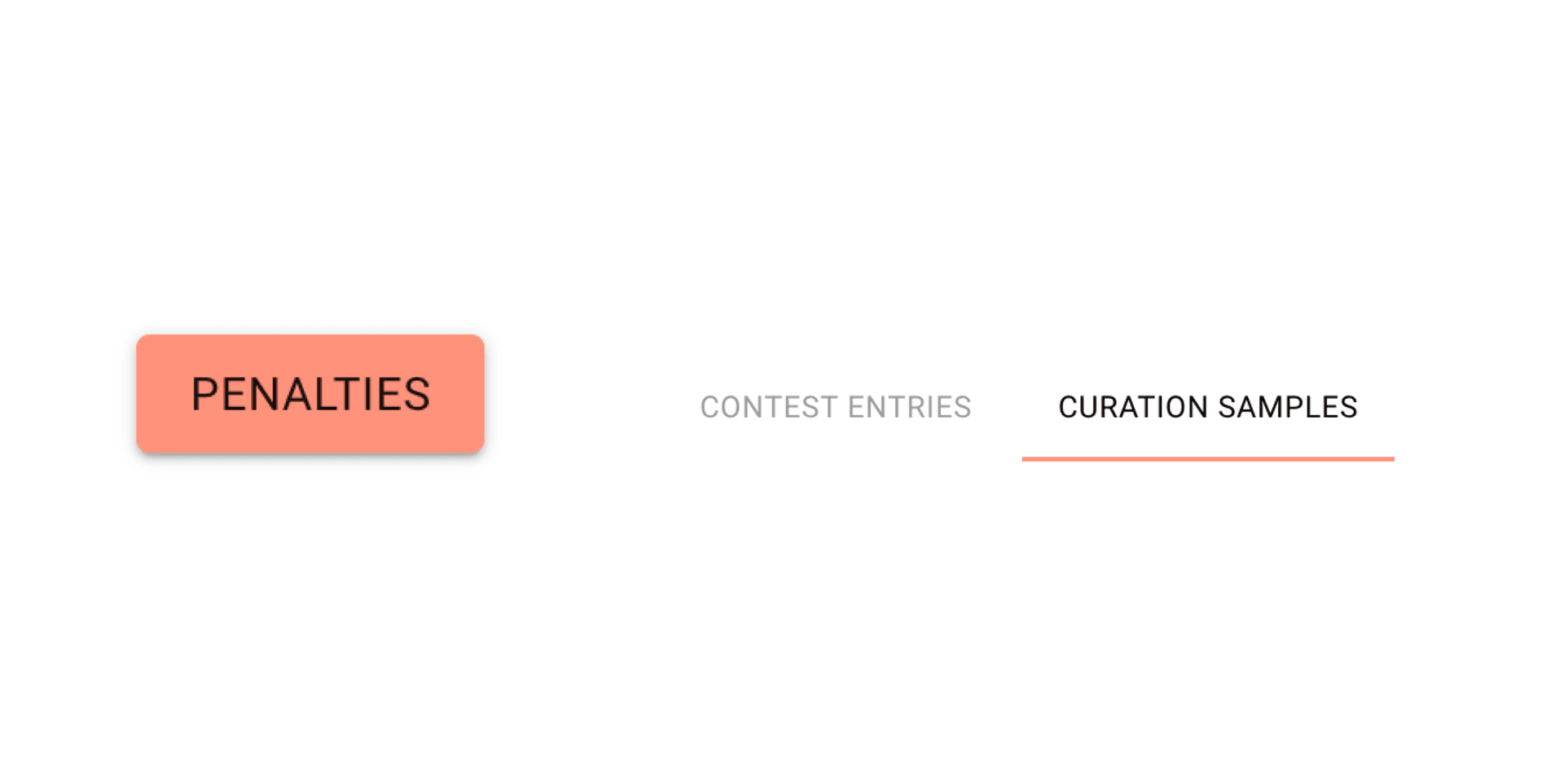

Here's what we shipped:

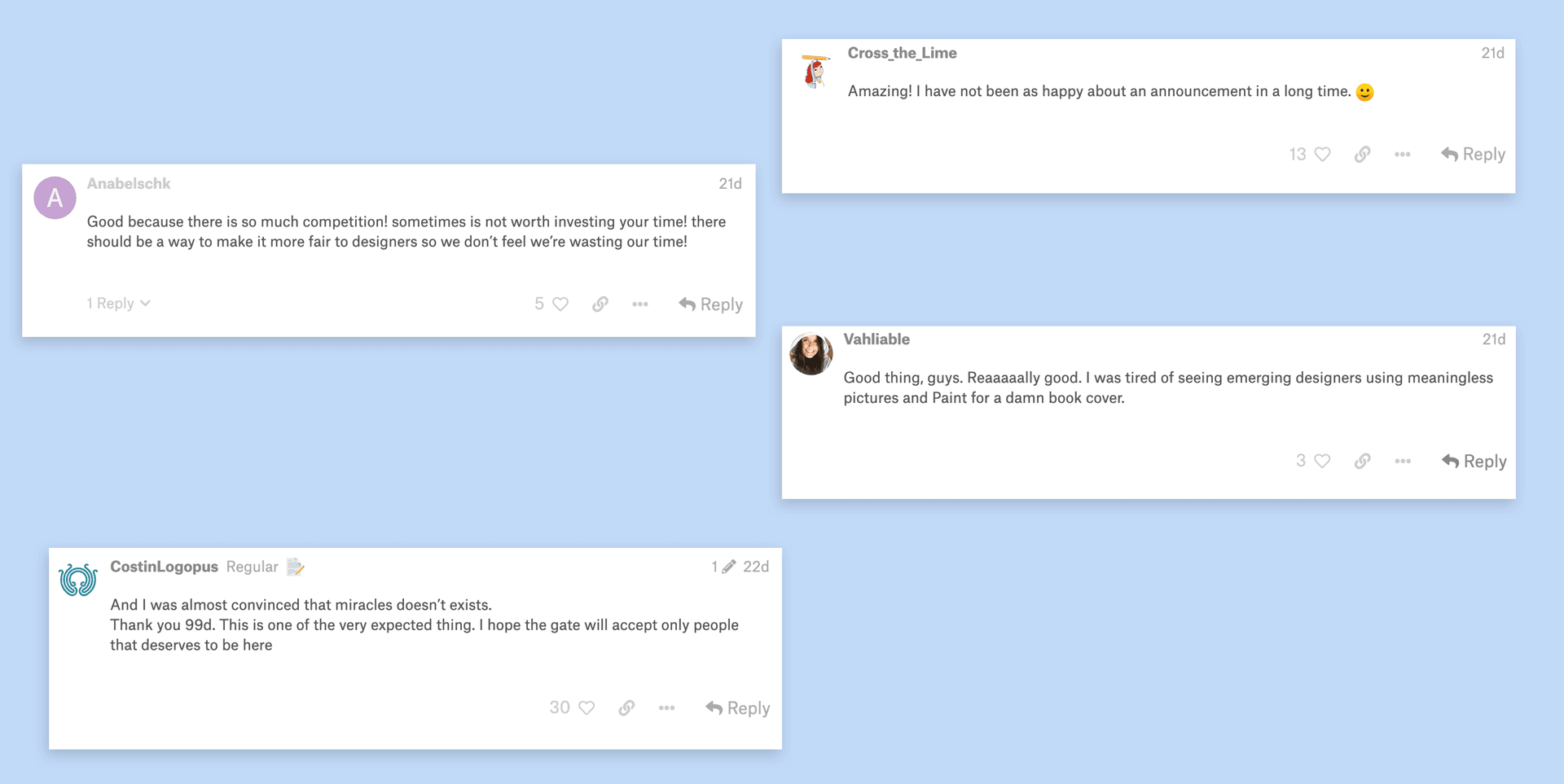

We also received an overwhelming amount of support and gratitude after announcing this new onboarding process in our designer community forum. Existing designers welcomed this change as it meant they wouldn't have to compete with low-quality designers again.

"Oh, this is very cool! I suffered a couple of times from unscrupulous designers. Now there is hope to avoid this. Thank you so much!" — Konstantin_Kostenko

"It is great to read this. More quality in term of ideas and education. This is going to put the bar a little higher." — AdrianKg

"Best platform forever." — tanlearn